Guest Blog – The importance of visiting a location

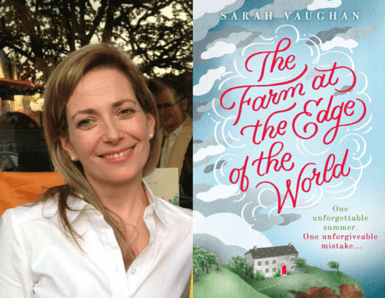

Why you shouldn’t rely solely on memory and other people’s experiences when writing a novel – advice from The Prime Writers‘ Sarah Vaughan.

There is a painting in Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, by the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Adriaen van de Velde, Landscape with cattle and figures, which is supposed to depict an Italian scene. There are olive trees and hills in the background that are loosely Italianate but something about it – perhaps the plump cattle or the lush trees in the foreground – could be more generically European.

There’s a good reason for this. Van de Velde spent most of his life in Amsterdam and never actually went to Italy. Instead, he drew on the work of his contemporaries Nicolaes Berchem and Karel Dujardin, who had visited, to paint landscapes cast in a warm Mediterranean light and conjure up an Italy more imagined than real.

I stumbled across this painting as I began to research The Farm at the Edge of the World, my Cornish novel set more than 350 miles from the Cambridgeshire village where I live. I wanted to write a book in which the location was so vivid, it was almost a character in itself. A place – desolate, unforgiving yet intensely beautiful – that inspired such powerful emotions its characters were reluctant to leave or felt compelled to return to it. And, if I could depict this sufficiently clearly, perhaps my readers would feel this, too.

At first I thought I could conjure up this setting by writing in part from memory. After all, I know this area of north Cornwall having been brought up in neighbouring Devon and having holidayed there most years. I could describe swimming in the ice-cold sea because I have done so for many summers; and recollect the flora and fauna, the smell of the rotting vegetation in the hedgerows, or of crushed camomile and tamarisk because these scents are so familiar. Google Maps was mentioned and I thought that this and the photographs dotted around my home could trigger memories that proved difficult to conjure. I would visit in the summer to collect some much-needed colour by which stage my first draft would be well underway.

Well, so much for that plan. I learned with my first novel, The Art of Baking Blind, that I am a sensuous writer. With my debut, I wrote about the smell, taste and feel of baking: the aroma of a buttery sponge; the texture of dough, the sharp tang of a rich tarte au citron or the warmth scent of a cinnamon-infused carrot cake. Describing all this was simple: all I had to do was bake and knead and taste. Capturing a Cornish hedgerow from a room in Cambridgeshire proved far more difficult. Worse – for someone who used to be a news reporter and has a deep fear of being inaccurate – it seemed like cheating.

And so I made the first of many trips. I had a good excuse. The Farm at the Edge of the World is partly set in 1943-4 and so I wanted to find some Cornish farmers who, like Will, my hero, had been sixteen or seventeen at that time. As a reporter for The Guardian, I loved getting people to tell me their stories and, after a little digging, I found a trio of octogenarian farmers willing to help. Sitting in their bungalows down twisting lanes; or in a long-slung granite farmhouse scented with wood smoke from an inglenook fireplace, I absorbed their stories and the sensory details with which to create the texture of my novel. Almost imperceptibly, these images – of gnarled tree trunks and moss-coated stonewalls; flagstone halls and storm-bent tamarisks – made their way in.

Inspired by the impact of these visits on my writing, I became obsessive about visiting precise locations. I traipsed to RAF Davidstow, a disused airfield, where I took a ride out into the centre of this spot on the edge of Bodmin Moor and imagined its night time loneliness; and to Bodmin itself, where a former orphanage sparked another plot detail and further scenes. I walked the beaches and cliffs I knew and loved and probed the depths of rock pools, noting blennies, crabs and jam-like sea anemones; I drove down ancient lanes – then quizzed Cornish wildlife experts about the particular oaks trees and flowers I’d found.

But it still wasn’t enough. The most intensely dramatic moment in the novel – and the emotional tipping point for one character – occurs on Bodmin Moor and, though I’d visited those farmers in hamlets skirting it, and raced over it for three decades, I still felt I didn’t know it sufficiently well. One of my characters embarks on a quest to find a half-remembered farmhouse and I couldn’t get these scenes right, sitting at my desk at home. I hadn’t captured the peculiar claustrophobia of high-banked hedgerows or of tiny villages hidden in the folds between tors. Nor was I sure about the smell: damp grass, musky bracken, honeyed gorse? My character, an 83-year-old with something to atone for, gets lost, and I half-wondered if I needed to do the same.

And so I did. For it’s hard not to become disorientated when you are relying on signposts that turn in contradictory directions and interpreting a Cornish mile as, well, a mile. And then the mist came down. A mizzle that made it impossible to see the tors I was searching for; that seeped through my trainers and into my bones; that reminded me of quite how bleak and inhospitable any moor can become.

Daphne du Maurier came up with the idea of Jamaica Inn when she got lost in the mist while riding – just a few miles from where I was. And as I climbed out of tiny Blisland towards St Breward – the area in which Poldark‘s farmhouse in the recent BBC TV series was filmed – I became similarly disorientated by a visibility that, at best, was poor. Incapable of seeing any farmhouse, or even the track in front of me, I had to stop still. It was just me, the relentless rain, and some Highland Cattle grazing amongst the gorse.

I had wanted atmosphere; a sense of place that was almost tangible; images which would fill my notepad and fuel me as I completed this particularly tricky draft. And here it was. Shrouded in the mist, I scrawled furiously; and, when the mist lifted, found that other famous du Maurier moorland setting, Altarnun.

It was time to head out. Back to the wildness of the open moor that encapsulates the darkness that seeps into my novel; and, ultimately, back to Cambridge, to decipher my reams of notes and to recapture the variety of Cornwall: its moor, cliffs and shoreline; its fields of barley and briar-filled hedgerows; and the Atlantic, pounding petrol-blue and foaming against its rocks.

I learned from this experience that it is no good my trying to take shortcuts: reading others’ descriptions of my chosen location, or even relying on photographs to trigger my own descriptions. I need to immerse myself in my novels’ settings from the start. Doing so gives me the confidence to write at the start, and inspires me to carry on writing persuasive, and I hope credible, prose.

I suppose what I’m trying to say is that I’m no Adriaen van de Velde. Painting in 1664, he had a pretty good reason for not venturing from Amsterdam to Italy. As a twenty-first century author, writing novels set in Britain, I have no such excuse for not immersing myself in the settings I describe.

My next novel is partly set in Westminster – where I used to work – and partly in Oxford, where I was a student. I remember such settings clearly; I know them well.

But I’ve still gone back. And it’s by sitting in the public gallery of the Commons or by meandering through the quads and libraries where I spent three years, that my characters have begun to whisper their stories – and that my novel has come alive.

The Farm at the Edge of the World is available to purchase online and in all good bookshops; Hardback: 17.99, EBook: £16.99.